“We’re Not Allowed to Hang Up”: The Harsh Reality of Working in Customer Service

In their own voices, seven customer service representatives reveal what it’s like being caught between abusive callers and demanding employers.

Last year ProPublica wrote about the world of work-at-home customer service, spotlighting a largely unseen industry that helps brand-name companies shed labor costs by outsourcing the task of mollifying unhappy customers.

As we reported on the industry, we invited current and former customer service representatives to contact us. They did. We heard from more than 100 and interviewed dozens. Often, their stories disturbed us. One woman, afraid to take a bathroom break, kept a jar under her desk in case she needed to urinate. Another, afraid to call in sick, paused calls to vomit. A third, afraid to hang up on a customer, didn’t know what to do when she realized a caller was masturbating to the sound of her voice.

These accounts captured how agents are simultaneously ubiquitous and invisible. Customers talk to them all the time but know little about their work conditions.

So we’re providing accounts from seven agents, many of whom describe the experience of being caught between abusive callers and corporate directives to appease. These seven are highly representative of the 100-plus agents we heard from, as well as the agents we interviewed in our first article. The agents, including some who told us they love their setups, laid out common themes, describing problems that people at various levels of the industry, including managers, have told us are endemic. We’ve also found echoes of these complaints in lawsuits and arbitration claims. Abusive callers are such a concern that, a few years ago in Canada, a union for telecommunications workers launched a campaign called “Hang Up on Abuse.” Airbnb, recognizing the emotional strain of taking such calls, offered their in-house customer service agents free therapy sessions.

The reps we spoke to needed these jobs, which allowed them to work from home even before the pandemic. They included people with disabilities, caretaking obligations or limited opportunities in rural towns. Recruitment ads touted flexibility and the chance to be your own boss. But many agents discovered the roles came with limited hours, close monitoring and strict performance measurements that put them in constant fear of losing their jobs. A Department of Labor investigator concluded that one contractor, Arise Virtual Solutions, exerted an “extraordinary degree of control” over agents.

Most customer service agents are women. Many describe being sexually harassed. One said a caller told her, “I really like the way you type.” Their work belongs to a grim history of women in outsourced roles stretching back to the piecework manufacturing era. A half century ago, temp work exploded, driven by companies hiring women to cut costs compared with full-time employees. These magazine ads from 1970 and 1971 show how women temps were viewed at the time, and the attitudes have certain parallels to how customer service agents are viewed today. While many agents work full time, a growing segment are independent contractors who don’t get paid holidays, vacation time or fringe benefits.

In the accounts below, most of the agents asked not to be identified, citing nondisclosure agreements that are common in the industry. (To work for some companies, agents must sign NDAs before they can even accept the job.) We’ve condensed for clarity and verified details wherever possible, collecting Facebook screenshots, email exchanges, company performance review forms, tax records and other proof of employment, along with contemporaneous recollections from agents’ relatives or friends. But there were instances in which we couldn’t get such documentation, owing in part to the premium placed on privacy and security by the companies. Some agents said they weren’t even allowed to have their personal phone in their workroom while helping customers. Some lost access to their email and the company platform when they quit or were fired, and they hadn’t made copies or screenshots beforehand. In every case we invited the companies that these agents worked with to comment.

Christine Stewart has social anxiety and depression. “I have a really hard time being out in public,” she said. She wanted to work from home, so she became an independent contractor for Sykes from 2017 to 2018. The company bills itself as “a leading provider of multichannel demand generation and customer engagement services for Global 2000 companies.” At Sykes, she helped customers using Intuit’s TurboTax.

“I was actually sick one day, I called, they have a supervisor line, and told them I was going to be [out] sick. And without actually saying it, the lady said, you’re going to be in trouble if you don’t show up. And me, I don’t like to get in trouble at work, I’m a good employee. I went to work. I kept hitting my mute button every time I had to throw up.”

During training, she said, “they told me if you wanted to work nights, you could work nights. If you want to work days, you can work days. Once you finish the training they’re like, ‘This is your schedule.’ I said I can’t work that and they were like, ‘Well, this is the schedule, and if you can\'t work the schedule, you don’t want the job.’ I was like, ‘I need the job, I do want the job.’ I said, ‘I can do 8 a.m. to 12 p.m.’ They wanted me to do 12 to 12. I have to get my kids on the bus in the morning, I was like, ‘I need to take a five-minute break when the bus pulls up.’ Even that was a huge problem for them. They would say, ‘You can’t keep taking these five-minute breaks.’”

Customers berated her. “One person called me the C-word. I’d call my supervisor. They’d say, ‘Calm them down.’ … They’d always try to push me to stay on the call and calm the customer down myself. I wasn’t getting paid enough to do that. When you have a customer sitting there and saying you’re worthless … you’re supposed to ‘de-escalate.’”

“There can be no background noise, no nature noises or cars passing by. I had a den. I had to insulate my den,” she said. (To confirm the expense, she shared a tax form with ProPublica that showed a $100 deduction.) “I had to turn the AC off; you could hear the AC blowing. They called me out on that. When I was training, the lady said she could hear the air conditioner in the background.”

One time, she said, “my kid broke his hand.” She dropped her call, dropped everything, to help him, but then she needed a story, because, she said, had she told her supervisors the truth — that her kid broke his hand and needed her help — “I would’ve gotten in trouble even if I had a hospital note.”

“I said my internet went down. I pulled the plug on everything, because it was their equipment. ... I didn’t know if they had any kind of monitoring software that wasn’t on the webcam or anything. It was better not to take any chances and unplug the whole thing.”

Intuit told us that it “engages with vendors” able to deliver “flexible support,” and that it is “dedicated to providing a safe, ethical, and inclusive workplace for all of our employees and vendor workers.” (See the full statement.)

Sykes did not respond to requests for comment.

She needed money for a medical procedure, so, during the pandemic, she began working for Liveops as an independent contractor, helping customers for Bath & Body Works. She worked from home.

For online orders, Bath & Body Works allows shoppers to use just one promotion per order. A customer, for example, can use a code to knock down the price of a particular item, but they can’t combine multiple codes. Customers can get upset when this is explained to them.

“We encounter customers who ordered the wrong items and want us to send them the right items for free. We receive calls from customers who have had their packages stolen. And then we get customers all the time who find out we don’t sell a particular fragrance anymore, and they can be just incredibly abusive.”

“I may as well say it out loud. We get called bitches all the time. One woman called me a ‘stupid fucking cunt.’”

“It can wear on you. We’re not allowed to answer back in the same way, nor are we allowed to hang up on them. Nor can we hang up on them after giving them one warning. The policy I am told is, we’re not allowed to hang up on any customer under any circumstances, even if they question our race or ethnic background or anything like that. My understanding is that we’re not even allowed to give people a warning.”

“We have to sit there basically and listen to these people until they run out of steam. It’s like they don’t see us as a person.”

With the pandemic, she said, a lot of agents are young women who lost their jobs and are desperate for anything. A lot of her fellow agents are Black women. “I’ve heard them say they were called ‘stupid n-----,’ ‘you stupid Black bitch.’”

While some customer service reps are pressed to work more hours than they want, she got too few. Last fall, she signed up to work for four and a half hours during one day. She was paid 31 cents per minute of talking time. So when she wasn’t getting calls, she wasn’t getting paid. For those four and a half hours, she said, she sat there with her headset plugged in.

“No calls in those four and a half hours. Nothing. … I got some personal budget stuff done. Surfed websites unrelated to work. Familiarized myself with products on the website. I hate to say it, but I think I dozed off at one point.”

Were there other days in which you got no calls? we asked.

“Oh, yes.”

“How many?”

“I lost track.”

Liveops has quality auditors who listen to at least four of an agent’s calls per month, she said. They score agents using an audit form, which she shared with ProPublica. It says agents should make a “connected recommendation for each opportunity throughout the interaction” based on the customer’s orders. Say a customer buys soap. The agent should ask, “Did you want a soap holder, too?” If a customer buys candles, the agent should also pitch candleholders.

“A customer calls to say, ‘Hey, I didn’t get my package.’ So I’m supposed to say, ‘Hey, do you want to buy some more products when you still don’t have your package?’ Oh, for crying out loud. Really.”

The audit form has 20 questions. They include: “9. Did the agent compliment the customer’s selections, reassure about the fragrance choices and/or give general positive reinforcement about the items? … 18. Did the agent apologize when necessary, show empathy and/or recognizes customer emotion? 19. Did the agent let the customer know that we have ‘heard’ them, that we genuinely care, and did the agent remain engaged throughout the entire interaction?”

A Liveops document said that if an agent’s scores fall within the “unacceptable” range for three months in a calendar year, “the agent may be subject to removal from the program.”

She said she recently received an email saying she had used profanity on a call, so Liveops was terminating her contract. She didn’t remember saying anything profane. The company provided no recording for her to listen to. She emailed Liveops and called corporate to ask for details or a chance to hear whatever it is she was supposed to have said, but she got no response. (She said she didn’t make copies of these emails before her email account was closed.)

“No appeal,” she said.

Liveops told us that it does not comment on specific clients or agents, but said in a statement that agents choose their client programs and “have the freedom and flexibility to work around their lives.” The statement added: “All client programs have their own unique process for handling and dispositioning unproductive calls and significantly upset clients. There are controls in place to ensure that, to the extent possible, all calls are professional, and no customer or agent is subject to verbal abuse.” (Read Liveops’ full statement.)

Bath & Body Works did not respond to requests for comment.

She worked as an independent contractor for Arise Virtual Solutions, a company that bills itself as a pioneer in the work-from-home industry.

Customers, she said, “get mad at us. They start cursing at us. They start threatening to report us to the main office.” One customer, she said, told her he was going to keep her on the line until he got what he wanted; he “started with the F-word,” then apologized, then carried on. He “wouldn’t stop and wouldn’t stop” until finally, realizing the agent wouldn’t give in, he gave up.

At one time she handled calls from Barnes & Noble customers. “A lot of cursing, a lot of crying — crying — believe it or not. I’ve been called every name in the book. And I do mean from A to Z. Everything in between. I’ve been hung up on, threatened, told I’m going to lose my job. I had one woman tell me, ‘I hope you have a miserable day.’ You can’t laugh. I can’t laugh. I’m thinking to myself, ‘You ordered the Bible. You’re some Christian person?’ She’d ordered a Bible! Those are the worst! Those are the worst hypocrites! They scream, curse, yell, carry on, threaten. They’re the worst.”

“The women, their mouths are unbelievable. Or they start crying. They’re worse than the men. I’m like, ‘It’s a book, for God’s sake.’”

Arise told us that it does not tolerate harassment of any kind. (See the full statement.)

Barnes & Noble did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

She was employed by iQor (pronounced I-core) as a retention specialist and sales agent, taking calls from customers for Sprint (which has since merged with T-Mobile). She worked in a call center.

“If the customer is angry and wants to completely cancel, you have 14 minutes to resolve their issue, get them to stay and sell them a new phone,” she said.

A unit called workforce management would push agents along. One workforce management monitor would sit at a computer, checking the length of each agent’s call. Another would walk the floor. These two would communicate by walkie talkie, one alerting the other to any agent whose call was running long.

“At 10 minutes you had somebody tapping on your shoulder. At 12 minutes you had someone tapping on your shoulder and saying, ‘Wrap it up, wrap it up, wrap it up.’ At 14 minutes, ‘What’s going on? You need to wrap this up. You need to move on.’”

“We had this guy who would run around on the floor yelling, ‘Move it along, people, all hands on deck, move it along, move it along.’”

Agents would have management in one ear and customers in the other. Customers would often be insulting, sometimes shockingly so.

She remembered one customer in particular. “He was very, very upset. And it’s personal. You get called names. ‘I hope you fucking die.’” Another Sprint customer told her: “‘I hope when T-Mobile takes over, you all lose your fucking jobs, your fucking families, your fucking homes, and you all kill yourselves.’”

She said she was not allowed to hang up. Only a supervisor could do that. “Where’s the line where you no longer have to take that?” she said. “I spent more than one instance in the bathroom, crying, then shaking it off and going back to work.”

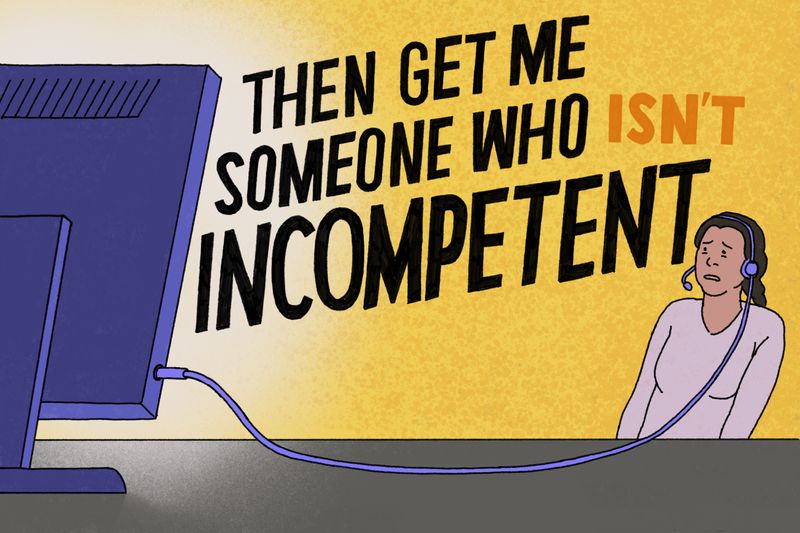

“I’m pretty thick-skinned, and I had nightmares. It beats you down. Everybody is angry. Eight out of 10 calls, they’re angry and they’re cursing by the time they get to you. Usually it’s the men who make it personal. That’s why I coined the term AngryWhiteManistan. ‘I have another resident of AngryWhiteManistan here.’ They’ll say things like, ‘Well, then, you better get me someone who is not incompetent.’”

In her nightmares, she said, she would be doing some mundane task, such as making dinner in the kitchen, when the phone would ring. She’d pick up and hear: “Are you done yet? We need to move on. We need to move on. We need to move on.”

T-Mobile, which merged with Sprint in 2020, told us it wouldn’t comment on Sprint’s prior practices. Since the merger, T-Mobile said, it has taken steps “to align T-Mobile’s Care practices across our team and all our partners to our award-winning Team of Experts (TEX) model, which heavily prioritizes customer and agent experience over more traditional call center metrics.” The company’s statement added, “We have a long-held policy that all of our experts do not have to tolerate abusive speech or behavior.” (Read the company’s full statement.)

IQor did not respond to requests for comment.

She’s lived in “many, many states” and worked in many call centers. Now she lives out west in a rural setting where jobs, and options, are scarce. A few years ago she found a job that lets her work from home. She started as an agent at Convergys (since acquired by Concentrix), then became a supervisor.

“It’s just enough of a wage that you’re going to be ineligible for most public support. I’m not eligible for any financial aid whatsoever. And yet I go to the food bank every month because I don’t make enough money. … I don’t go to the doctor, even when I should.”

She said the job attracts a lot of new parents. And retirees. And people with medical issues. She said that in her experience, the turnover is “tremendous.” Within months, many people get fired, or “termed,” short for terminated. “We fire more than they resign. A lot more.”

Most firings are over attendance. What counts as an attendance infraction? “Anything. It doesn’t matter if it’s in your control or not. … Your power goes out and, bam, you’re absent. ... Doesn’t matter if you had a hurricane.”

“You don’t know if you’re going to have a job tomorrow.”

Once, as a supervisor, she listened to a recording of a call that had been made to an agent working at home, answering calls from customers for DirecTV. “DirecTV had a policy, you never hung up on a customer, ever. You simply weren’t allowed to, no matter what they said.” (ProPublica interviewed another agent who also understood this to be the case.)

“There was a guy who called in and masturbated on the phone. It was awful. … Just imagine being a woman in your office in your home, alone. And here’s this guy doing this, and it takes you a few minutes to figure out what that sound is, and when you do you’re horrified, and you don’t know what to do. All you know is, you’re not allowed to hang up the phone. That would be horrible. I felt so terrible for her.”

The agent, crying, asked if she could quit for the day without an attendance infraction. “We had the recorded call, it’s not like it was ever in doubt. My boss was a man, at first he didn\'t understand why that was an issue.” He didn’t understand why the agent was so troubled. “I had to go to HR to get them to explain to him why it was an issue.” Only then could the agent stop taking calls.

Convergys was acquired by Concentrix in 2018. Concentrix said it does not disclose details about current or former staff out of respect for their confidentiality, but said in a statement: “We recognize that the work-at-home environment isn’t for everyone. … We take the health and safety of our staff very seriously and do not have a no hang-up policy. Our staff are given extensive training to manage each interaction with techniques to deflect and diffuse situations should they arise. If subjected to harassment or abuse they are trained and empowered to end the conversation.” (See Concentrix’s full statement.)

DirecTV told us: “The allegations are disturbing. We suggest you contact the agent’s employer.” In a written statement, the company said: “We don’t tolerate, and we don’t expect our vendors to tolerate, harassment of any kind. We have policies and procedures in place for our employees to escalate inappropriate customer interactions and the ability to terminate any customer interaction if and when that becomes necessary.” A DirecTV spokesperson said in a phone call that “to the best of our knowledge,” the company has not ever had a no-hang-up policy.

She’s in her 60s and wanted a work-from-home job to keep her family safe during the pandemic. She saw a company called Arise Virtual Solutions mentioned online, but she was skeptical. She would be an independent contractor, required to absorb substantial startup costs. (ProPublica’s previous article on customer service noted that Arise’s agents often spend more than $1,000 on training and equipment.)

Then she saw Bob Wells, a real-life nomad featured in the movie “Nomadland,” talking about Arise on YouTube. She decided to give it a chance. “I was like, ‘I need work.’ … I’d kind of given up on finding something more legit, frankly, because of the pandemic. So it was a pandemic Band-Aid for me.”

She answered calls from customers for Home Depot. One, a nurse’s aide, had ordered a portable toilet for a client. “This woman was like, ‘I have a 90-year-old lady who needs this thing like, yesterday, and you haven’t delivered it for three weeks, what is your problem?’” To the agent, this was urgent. “When it became a humanitarian issue, and there were plenty of humanitarian issues, especially during the pandemic,” she would send the matter to people above her, who would then send it to Home Depot to do something. The customer’s problem might then be resolved. “But my stats would go down,” she said, because she hadn’t resolved the matter herself. (She shared Arise’s performance metrics with us.)

On days when the phone didn’t stop ringing — and there were many — she couldn’t step away from her desk. “I had a bottle I kept under my desk in case I had to urinate. I never used it, but I had it there if I needed it. I’m in my 60s. … There could be an emergency.”

The work was isolating. She joined Facebook groups (and provided screenshots to ProPublica) and began to talk with other frustrated agents. She realized she was among the few white women in her work cohort. And she realized customers were nicer to her — an immigrant with a British accent. “When I first came to this country, I couldn’t believe people could tell the color of a person over the phone. That was a culture shock. ... When people are calling in, I think they find it easier to yell at a Black woman. … I’m not the most evolved person, but I began to look at the work through a racial lens. ... I answered the phone, and there were people who called, and right at the beginning of the call, they were full of white-hot rage.” Then they would hear her accent. “Well, the amount of comments I got from people who were like, ‘Wow, they’ve got classy people here!’ … I was born in a British colony. People think I’m a butler or a classy servant.”

Home Depot spokesperson Margaret Smith told us the company uses an escalation process designed to help agents handle difficult calls. “If a customer becomes irate or disrespectful, we ask the associate to either have their supervisor take over the call or transfer the call to the resolution queue,” she said. Agents who use this process are not supposed to be penalized, she said. (Read Home Depot’s full statement.)

Arise provided us with a statement about its network of agents, whom it calls service partners. “Arise does not tolerate discrimination or harassment of any kind,” the statement said. “Service Partners interacting with individual customers through the Arise® Platform are protected by both client and Arise policies and processes that include the ability to disconnect callers without penalty or transfer these calls to support resources if they are unable to de-escalate the situation.” (Read Arise’s full statement.)

Mara M. was a hairstylist and cosmetology teacher when her health began worsening. “Probably in about 2015, I started sleeping a lot. Any time I would stand up I would get really dizzy, really lightheaded. One of the requirements to teach hair is to be able to stand. I couldn’t stand up. It was a walker and wheelchair for me. … I have postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.”

Mara eventually discovered Concentrix, a global customer service outsourcing company, while searching for work-from-home jobs on Indeed.com. She signed on at age 23, hoping she might be matched with a company that sold beauty products.

At her orientation three weeks later, Mara learned which account — that is, which of Concentrix’s corporate clients — she would be matched with. She would be working part time, doing video calls and live chats for Intuit. She would be helping people use TurboTax.

Mara didn’t have an office. But she did have a closet. So she turned her closet into an office. (She sent us photographs.) “They sent me a blue screen to put behind my chair,” she says. That way, customers wouldn’t know she was working from home, much less from inside her closet. She bought a computer, a monitor, a headset.

“We were not supposed to hang up. … You’re supposed to hear them out, then empathize with them, then acknowledge that the problem was made. I had tried all that. They say, you know, apologize, but the people stay angry.”

One customer called her, moaning. “I was very uncomfortable. I couldn’t tell if he was sick; I couldn’t tell if he was watching porn in the background. I just tried to get through the guy’s questions.” Afterward she told a friend that she thought the man on the other end of the line had been masturbating. (The friend confirmed this conversation.)

She learned that agents were monitored. “We had a webcam, and [the monitors] can see you through the webcam. … I’m not sure how often you were watched. But the trainer did say you should shut down your computer after your shift because they can still see you. I was like, that’s really Big Brother. … That freaked me out because I spend a lot of time in my room.” And she learned there were no built-in breaks for part-timers. “You can’t step away when you’re on the clock.” She said it felt confining, like her closet was a prison cell.

She struggled to answer questions about complicated tax forms. She would Google for answers in a different window while trying to look confident to the customer, who could see her on the video call. “I had a nightmare so bad that I’d wake up at 6 in the morning over this job. I cried. I’m a sensitive person, so a lot of people probably wouldn’t have cried. … I didn’t know what I was doing. … I was like, ‘I finally have a job, but I don’t know what the answers are.’”

Mara didn’t feel like she could quit. For the most part, she said, her metrics were high. But customers weren’t responding to survey questions about her performance. And her lowest score was her “doc rate” — documentation rate — which penalizes agents for not closing out a chat with a customer. They get credit only when a customer says, “Yes, you have answered all my questions.”

“Some people don’t answer back after they get the answers they need. For those types of chats and everything, we couldn’t close those cases. My doc rate dropped because ... I couldn\'t close the case on some of them.”

Eventually, Concentrix emailed to say that TurboTax wanted her off the account, citing “a review of stats … done over the weekend.” (Mara shared copies of the exchange with ProPublica.)

“I do apologize for the inconvenience,” a Concentrix representative wrote. “Please feel free to apply for other Concentrix accounts!”

Intuit told us agents are “provided training to end calls with customers should they encounter abusive or threatening behavior.” Its statement also said that Intuit establishes performance standards with vendors such as Concentrix: “Vendors — not Intuit — are responsible for ensuring those workers they engage to support Intuit’s customers or our account meet those standards.” (Read the full statement.)

Concentrix, which said it does not disclose details about current or former staff, told us, “We take the health and safety of our staff very seriously and do not have a no hang-up policy.” (See Concentrix’s full statement.)